As recently as a few years ago, complaints about blindingly-bright bicycle headlights were incredibly rare. Far more frequent and serious were complaints about cyclists without any lights, or with dim lights that could scarcely be seen, let alone give the rider enough light to see the road. That began to change with the introduction of high-powered, highly-efficient light emitting diodes. Super-bright LEDs provide more lumens per watt than any traditional incandescent or halogen light, and are far more durable as well. The LED revolution has made it easy and economical to buy bicycle headlights at least as bright as the low-beam headlight of a car.

With the undeniable safety benefits of

more-than-adequate headlights on bicycles has also come a rising tide

of complaints by other cyclists, pedestrians, and motorists about being

dazzled or blinded by bicycle headlights. In some quarters this

has raised calls for limiting the maximum brightness of bicycle

headlights to protect other road users.

But if cars can peaceably share the road with a pair of 1,000+ lumen headlights on the front of each, is it really brightness that's the problem?

For generations, car headlights have been

regulated to prevent dangerous

glare. When car headlight glare was first regulated, typical

headlights were dim and yellow by modern standards, plain old

incandescent filament bulbs putting out less than 700 lumens each --

many bicycles today have more headlight output than drivers used before

the introduction of halogen headlamps. Even so, when standard

sealed-beam headlights with beam cutoff were mandated in 1940, they

were hailed as "the greatest safety advance since the days of acetylene

lamps" by legislators concerned over accidents caused by headlight

glare.

Automotive headlight laws are enforced both at

the manufacturing level

and on the road under state traffic laws. Car headlights have

regulated beam patterns, a sharp cutoff on the top of the beam to keep

the light down on the road where it belongs. In the U.S., the

NHTSA actively enforces these standards for replacement headlights, as

seen in repeated action against illegal HID-retrofit kits in recent

years.

On the road, state vehicle codes require low-beam headlights to be aimed below level, and the rules of the road prohibit shining headlights in the eyes of oncoming drivers. For example, here in Washington State, the RCW requires that "There shall be a lowermost distribution of light, or composite beam, so aimed and of sufficient intensity to reveal persons and vehicles at a distance of one hundred fifty feet ahead; and on a straight level road under any conditions of loading none of the high intensity portion of the beam shall be directed to strike the eyes of an approaching driver;" and that "Whenever a driver of a vehicle approaches an oncoming vehicle within five hundred feet, such driver shall use a distribution of light, or composite beam, so aimed that the glaring rays are not projected into the eyes of the oncoming driver."

In most states, these rules apply only to

motor vehicles, not to bicycles or other nonmotorized vehicles.

In the United States, most bicycle headlights

available today have a plain, round beam pattern like a

flashlight. Some have narrower cones of light than others, but a

round beam has significant amounts of light above the bright center of

the beam.

Some bicycle headlights, however, have

regulated beam

patterns more like low-beam car headlights. When bicycle

headlights used relatively dim 2.4W incandescent bulbs, a shaped beam

put more useful light on the road. In countries with a

significant share of transportation by bicycle on segregated bicycle

paths, regulations have the same aim as car headlights, to promote

safety by keeping glare out of the eyes of oncoming riders. In

the 1970s bicycle boom. headlights from Germany were often prized for

their more-efficient distribution of the dim light provided by

tire-dragging 6-volt generators.

Even with today's bright LEDs, some lights

continue to use asymmetrical beam patterns to make more efficient use

of light. Below, for example, is the beam pattern of a Philips

SafeRide

LED headlight -- notice the sharp cutoff on the top of the beam,

keeping the high-intensity light below handlebar height. The

light intensity is also tapered, less intense near the bike so that the

more distant light isn't washed out by bright bright foreground

illumination.

A related issue is headlight aim.

Most riders aim their headlights below level, to illuminate the road ahead, like the low-beam headlight of a car or motorcycle. But some aim their lights well above level, out of a belief that this makes them more conspicuous to motorists or simple lack of consideration for other users of the road. For any motorized vehicle, this behavior would be illegal, but bicycle headlight laws in most states have not been updated since the age of dim 2.4-watt incandescent headlights. Rules usually specify some minimum distance at which the headlight is visible to others, but assume the light will be too dim to be a hazard to anyone.

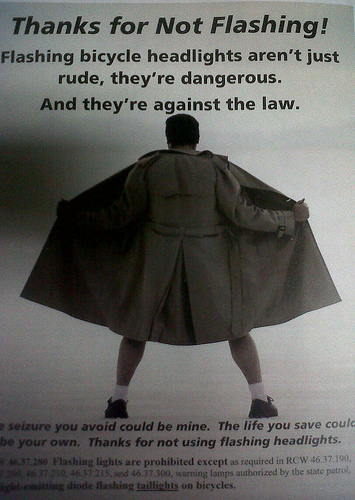

An added factor in many complaints against dazzling bicycle headlights is flashing or strobing lights. Many riders, aware of the conspicuity advantage of flashing tail lights, have also adopted flashing headlights. But a tightly-focused, high-power, white headlight beam is very different from a tail light. Strobing a headlight of 500 lumens in the eyes of an oncoming cyclist or motorist can be quite dazzling, and has been reported to trigger seizures in some photosensitive people.

Below, a poster I passed on the I-90 trail in 2012, asking cyclists not to use flashing headlights, and warning of inducing seizures:

The potential for seizures caused by bicycle lights has also been noted by some epilepsy advocacy groups and photo-sensitive cyclists. (While people with seizures triggered by flashing lights often cannot legally drive, this may increase the chance they will be exposed to non-motorized lighting, on multi-use trails or sidewalks next to roads with cyclists.)

Some bicycle riders, seeking to stand out in

traffic, use non-standard colors of headlights -- green, blue, red,

etc. It's true that unusual colors may be seen somewhat more

quickly by motorists. But that doesn't necessarily make them

safer. For safety, a cyclist needs to be seen and

identified as a vehicle. Motorists are trained and

accustomed to identifying standard lighting colors -- red is on the

back of vehicles; white is on the front; blue is for police, etc.

Motorists confronted with red on the front of a bicycle, or white on

the back of it, may respond to the color rather than the actual

direction of the bicycle.

Cyclists and motorists in many states have

begun suggesting legal restrictions on bicycle headlights. At the

opposite extreme from today's anything-goes headlight market in the

United States, Germany micro-manages bicycle headlights with very

detailed regulations that have stifled technological advances for many

years.

American cyclists would, in my opinion, be well-advised to get ahead of this issue with support for very clear, simple regulations such as those used for low-beam car headlights, requiring that "on a straight level road under any conditions of loading none of the high intensity portion of the beam shall be directed to strike the eyes of an approaching driver."

But, quite apart from legal approaches, there

are things ordinary cyclsits can do to encourage their peers to use

their headlights more responsibly.

For example, I've found that adding a large area of reflective trim on the front of my helmet cover makes it extremely obvious when the headlight of an oncoming cyclist or motorist is bright enough that I need to look away. (I've also had an oncoming rider complain that my "helmet light" was too bright, when in truth it was just returning a fraction of the glare he was throwing my way.)

It's also possible to encourage better

behavior by explicitly modeling it, such as shading or dimming your own

headlight when an overly-bright one is approaching.

This page written by Josh Putnam. Please feel free to email questions, comments, corrections, suggestions, etc.

© Joshua Putnam